There is a quiet courage in the work of re-seeing the world.

For many men, this work begins not with guilt or accusation, but with awakening — an honest recognition that much of what they were taught about love, success, and worth was filtered through lenses they never consciously chose.

Those lenses shape how they see women, how they see each other, and how they see themselves. To begin to notice those patterns is not weakness; it is the beginning of freedom.

This reflection is not about blame. It’s about understanding how culture shapes perception — and how men can reclaim their humanity by learning to see others, and themselves, more clearly.

The Inherited Lens: Hierarchy as Habit

Every man inherits a framework before he ever chooses one. From childhood, subtle messages define strength as dominance, emotion as fragility, and control as competence. These are not personal flaws; they are the scaffolding of culture itself.

Simone de Beauvoir described how societies often define men as the default — the doers, the decision-makers — while women are cast as the context, the mirror, or the support. This hierarchy doesn’t only limit women; it quietly confines men too. It isolates them from tenderness, empathy, and interdependence. It makes vulnerability feel like exposure rather than connection.

You can see this everywhere: in the workplace meeting where a man feels pressure to speak with certainty even when unsure; in the father who provides materially but hides his own exhaustion; in the friendship where warmth is replaced by banter because sincerity feels unsafe. These are learned reflexes, not truths about manhood.

Recognizing them isn’t self-criticism — it’s awareness. Hierarchy was never chosen; it was absorbed. Seeing through it becomes the act of rewriting it.

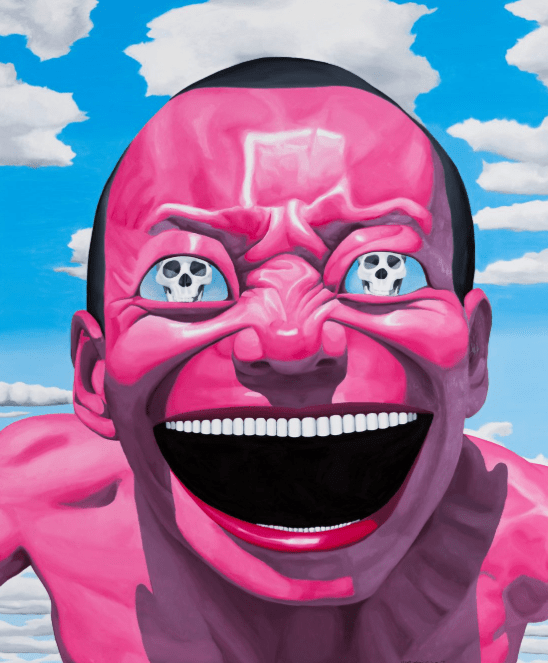

Objectification and the Loss of Depth

Objectification begins as a survival strategy — a way of managing complexity by reducing it to something we can control. It is not born from cruelty but from fear: fear of vulnerability, of rejection, of emotional overwhelm. For many men, objectification has been the only safe way to relate in a culture that punishes emotional openness.

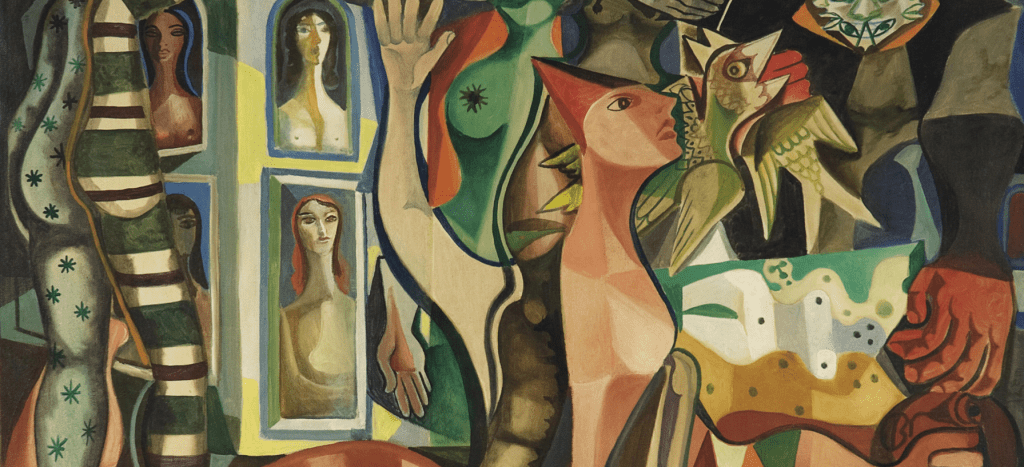

From an early age, boys are taught to notice beauty before they are taught to notice humanity. They are rewarded for pursuit, praised for conquest, and rarely shown how to look at another person without desire or evaluation. This conditioning trains the eye to flatten — to turn the infinite depth of a person into a surface that can be categorized.

In this sense, objectification is not merely about sex. It’s a perceptual habit, a narrowing of sight. It can show up in how a man views women, but also in how he views himself — as a role, a provider, a performer — anything but a being.

Simone de Beauvoir called this “the reduction of the Other.” The woman becomes not an equal subject but a mirror for male identity. Yet in doing this, the man also becomes diminished. He trades intimacy for control, authenticity for image.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy of perception helps us see why this is so damaging. When the gaze becomes detached, it severs the relationship between body and soul, between self and world. The person looking loses the capacity for connection — not because he is incapable of love, but because his way of seeing has been trained to avoid depth.

To unlearn objectification, a man must learn to look longer — to see the human being behind his reflexes. This doesn’t mean rejecting attraction; it means letting attraction coexist with respect, curiosity, and wonder. It means learning to feel without possessing.

When he does, something shifts. What once felt like temptation becomes tenderness. What once triggered guilt becomes gratitude. He begins to understand that seeing another person as whole is not restraint — it is freedom.

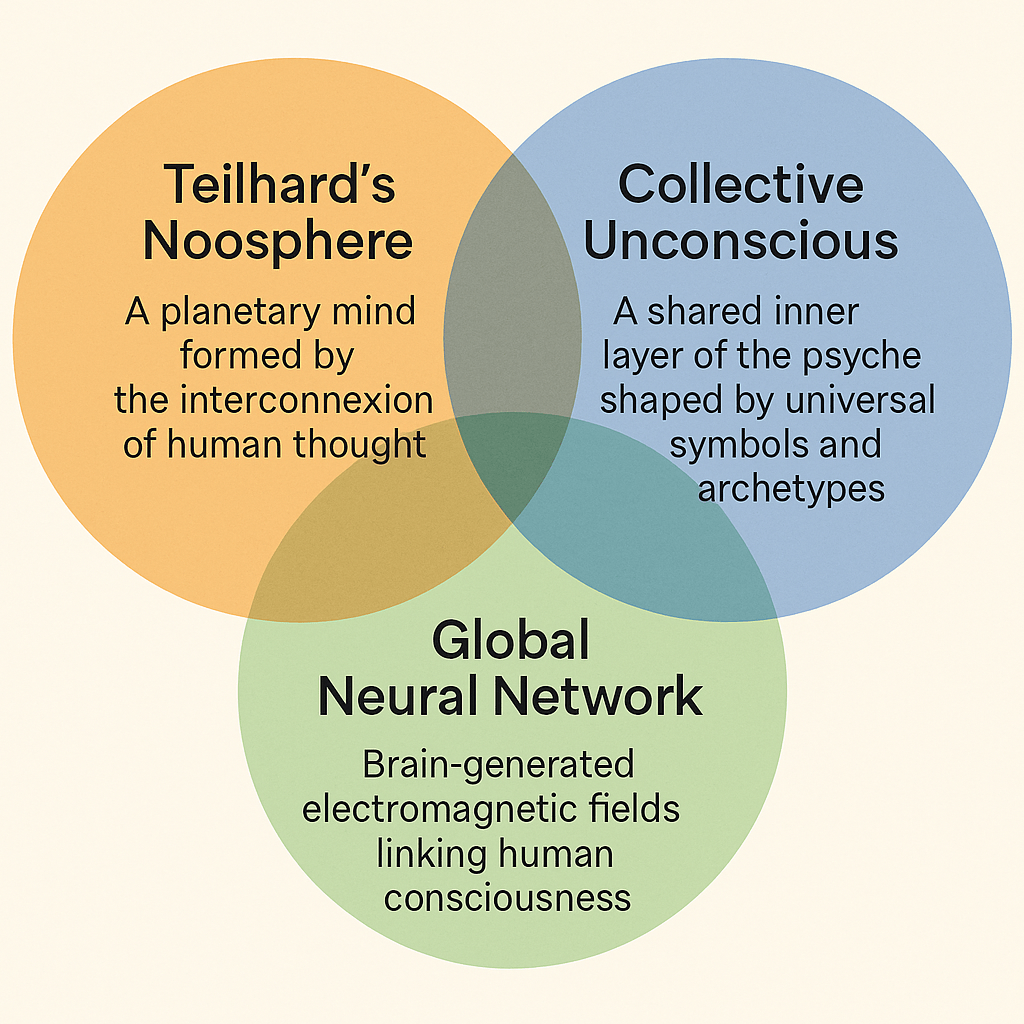

Seeing as Participation — Merleau-Ponty and the Embodied Gaze

Maurice Merleau-Ponty taught that perception is not passive — it is participatory. To see something or someone is to be in relationship with it. We don’t look at the world; we look with it. The gaze itself is a form of contact.

When men begin to realize how their perception has been shaped — by media, by trauma, by cultural training — it can feel unsettling. Yet that very realization reveals the possibility of transformation. Because if perception is learned, it can also be relearned.

In a digital world, where images flash faster than empathy can form, men are taught to evaluate rather than encounter. Pornography, advertising, and social media train the eye to scan for desirability or power, not humanity. But something shifts when a man looks longer — when he pauses to really see a person instead of a projection. A simple act of attention can reawaken empathy, restoring depth where habit had flattened it.

Merleau-Ponty reminds us that to look with awareness is to engage ethically. The gaze can wound, but it can also heal. Every time a man chooses to see with curiosity rather than consumption, he reclaims the living quality of perception itself.

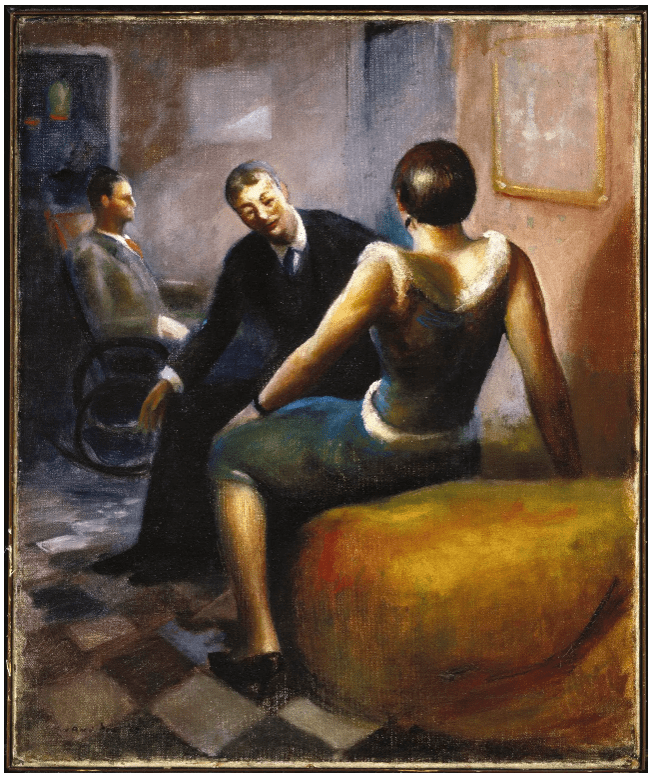

From Performance to Presence — Buber’s Call to Meeting

Martin Buber believed that all real living is meeting. He described two modes of relationship: I–It and I–Thou. In the I–It mode, people and things are treated as objects — useful, measurable, and often disposable. In the I–Thou mode, we encounter others as full beings, not categories.

Most men are conditioned to live in the I–It world. The culture of performance rewards decisiveness and control. A man learns to evaluate rather than experience — to measure his life by outcomes rather than intimacy. But this comes at a cost.

He might find himself sitting across from his partner but thinking about work; scrolling his phone instead of connecting at dinner; performing competence instead of expressing care. These are not failures of character — they are symptoms of disconnection.

When presence replaces performance, the dynamic changes. Listening becomes more powerful than solving. Eye contact becomes more healing than explanation. A man who learns to meet others without agenda steps into what Buber called the sacred space of encounter. In that space, both people are transformed.

Levinas and the Responsibility of Seeing

Emmanuel Levinas argued that ethics begins not in law but in encounter — in the face of another person. The face of the Other calls us to responsibility simply by existing. To truly see someone is to recognize their inherent dignity.

For men, this offers relief as much as responsibility. It removes the pressure to dominate or fix and replaces it with the invitation to care. Seeing becomes moral participation.

You can feel this difference in small, ordinary moments — choosing to stay in a difficult conversation rather than withdraw; recognizing the humanity in someone suffering on the street instead of looking away; responding to conflict with curiosity rather than defense.

Levinas reminds us that the eyes are ethical organs. To look at another human being and allow yourself to be moved by their vulnerability is not weakness; it’s moral strength. Presence itself becomes a form of protection — both for the other and for one’s own integrity.

The Desire to Care — From Protection to Partnership

Many men carry a sincere and beautiful desire to care for women — to protect, to support, and to make life easier for those they love. At its root, this impulse is not domination but devotion. It grows from empathy, loyalty, and the instinct to safeguard what matters most. Yet in a culture that confuses care with control, this tenderness can become distorted.

Protection can quietly slip into paternalism. Support can become substitution. Even when motivated by love, men may find themselves doing for women rather than walking with them — making decisions, offering advice, or solving problems in ways that unintentionally overlook or undervalue women’s insight and capability.

This isn’t cruelty; it’s conditioning. For generations, men were taught that their worth lay in their ability to provide, to lead, and to fix. Women, by contrast, were often expected to accommodate, nurture, and defer. When those scripts meet, imbalance hides beneath the surface of affection. The woman’s competence and wisdom can go underrecognized, while the man’s care goes unacknowledged for its sincerity. Both feel unseen.

As Simone de Beauvoir observed, inequality often persists not through open conflict but through subtle assumptions. The deeper problem isn’t overprotection; it’s under-crediting.

True care, as bell hooks reminds us, is not hierarchical. Love that liberates gives as much as it listens. It allows women’s voices to lead as often as men’s and recognizes that strength belongs to both.

Buber’s I–Thou relationship captures this transformation. In the I–It mode, care becomes management — an effort to ensure safety or order. In the I–Thou mode, care becomes communion — a willingness to stand beside another person, not above them.

Levinas would add that genuine responsibility honors the other’s autonomy. The face of another does not ask to be guided, but to be recognized. The ethical act is not to decide for her, but to stand with her — to affirm her full humanity.

When men care in this way, they do not lose their protective nature; they refine it. Care becomes partnership, protection becomes reverence, and love becomes equality embodied. This is not the end of masculinity — it is its maturity.

Fatherhood and the Protector Reflex

In family life, the desire to protect often reveals itself most vividly in moments of conflict. A father might hear his child speak sharply to their mother and instinctively raise his voice: “Don’t talk to your mother like that!”

On the surface, this seems noble — a defense of respect and love. Beneath it, though, is a deeper question about how protection and partnership coexist.

When a father steps in this way, he is often not defending his wife as a fragile being but defending the sacredness of respect itself. Yet when that defense takes the form of control — of correcting through dominance rather than connection — the message subtly shifts from “Respect your mother” to “Your mother needs my protection.”

This difference matters.

Children quickly internalize who holds authority, empathy, and voice in a home. When protection overshadows partnership, the mother’s authority can be unintentionally undermined — as though she cannot stand in her own strength.

True partnership looks different. It sounds like a father who, rather than commanding silence, models presence: “Hey, something feels tense here — let’s all take a breath.” It’s standing with his partner rather than over her. It’s backing her up without eclipsing her.

bell hooks wrote that love requires mutual recognition of power, not its suppression. In family life, this means protection transforms into respect when both parents’ voices carry equal weight.

Children learn best not from being silenced but from witnessing emotional integrity — a father’s capacity to protect without overpowering, to model firmness without hierarchy.

When a man learns to pause before stepping in — to ask whether his action preserves connection or reinforces control — he redefines protection itself. It becomes not an act of defense but of devotion. He is no longer guarding his partner; he is honoring her.

Love as Liberation — bell hooks and the Courage to Feel

bell hooks described love as “the practice of freedom.” She saw love not as sentimentality but as the daily discipline of seeing others as whole, autonomous beings rather than extensions of one’s ego.

For men, this redefines power entirely. Love becomes an act of courage — the strength to stay open, even when the world tells you to harden. It’s not about losing control, but about letting go of control as the measure of worth.

You can see this transformation in the father who learns to express affection that once felt awkward; in the friend who admits fear instead of hiding it behind humor; in the partner who listens without defensiveness and recognizes that understanding, not winning, is what restores connection.

Love, in this sense, is a way of seeing — an attention that liberates both the one who looks and the one who is seen. When men love in this conscious way, they don’t lose their strength; they deepen it. They move from protection to partnership, from guarding to giving.

Inheritance and Healing: The Work of Unlearning

Many men grew up in environments where tenderness was conditional, where strength meant silence, and where love was tangled with control. Those lessons don’t disappear with age; they live quietly in the nervous system, shaping how men relate to others and themselves.

To unlearn that inheritance is not to reject one’s past — it is to reinterpret it. Healing means understanding that discipline is not the same as distance, that leadership does not require hierarchy, and that emotional expression is not weakness but maturity.

In the workplace, this healing might look like leading through listening instead of intimidation. In fatherhood, it might look like gentleness that coexists with structure. In friendship, it might look like vulnerability that builds trust rather than shame.

When men begin to integrate these truths, they reclaim parts of themselves that were never lost — only hidden. They become whole enough to love without fear.

Practices for Embodied Change: How Men Can Relearn the Art of Seeing

Insight without practice can become another form of avoidance.

To truly shift from hierarchy to empathy, from performance to presence, men must not only think differently but live differently.

Change happens not through shame or pressure but through embodied, repeatable habits that retrain perception, soften the nervous system, and make love practical.

1. Begin with Awareness, Not Judgment

Pause before reacting. Notice the impulse — the tightening in the chest, the scanning eyes, the urge to control. That moment of recognition is not failure; it’s awakening. Ask yourself, What am I protecting right now — my image or my connection? Let awareness replace self-criticism.

2. Reclaim the Body as an Ally

Presence begins in the body. Practice somatic grounding: place a hand on your chest or abdomen and breathe deeply before responding. Movement and mindfulness reconnect emotion and embodiment, restoring empathy.

3. Practice “I–Thou” Encounters

Make eye contact in conversation. Listen to understand, not to fix. Replace performance with presence — say, “I don’t know” or “I care.” Each small act of genuine meeting resists dehumanization.

4. Expand the Lens

Ask, Who or what am I overlooking? Notice when hierarchy hides in habits — when you value voices like your own more than those that differ. This questioning is the essence of ethics.

5. Redefine Strength

True strength is emotional honesty. Practice admitting fear, confusion, or tenderness. Share one emotion daily that you’d normally suppress. Vulnerability builds, rather than weakens, trust.

6. Practice Gratitude for Growth

At day’s end, name one moment you chose connection over control. Transformation happens in these micro-movements of awareness and care.

7. Seek Dialogue and Mentorship

Healing thrives in community. Find other men committed to inner work. Speak the truth aloud. Brotherhood grounded in honesty is one of the most radical forms of resistance.

8. See Through Love

Love is a practice of perception. When you see someone, choose appreciation over possession, witness over withdrawal. Love with your attention — that’s how seeing becomes healing.

The Heart of It

Objectification is not hatred; it is disconnection. It’s the cultural habit of narrowing our vision until others — and we ourselves — become smaller than we are. But men are not bound to that way of seeing. They are capable of extraordinary empathy once they remember that to see is to touch, to meet, to love.

To see through Merleau-Ponty’s eyes is to know the world as living and responsive.

To see through Beauvoir’s critique is to notice how power distorts perception.

To meet through Buber’s lens is to rediscover the sacred in relationship.

To answer Levinas’s call is to let compassion become the first reflex.

And to love as bell hooks urged is to live with open eyes and an unguarded heart.

The opposite of objectification is not shame — it is presence.

And presence, practiced daily, is how men learn to see — and live — with love.

Author’s Note:

bell hooks styled her name in lowercase letters to emphasize the message over the self — a symbolic act of humility and a rejection of hierarchy. The lowercase “bell hooks” honors that intention and keeps focus on the spirit of her work: to center love, liberation, and consciousness over ego.

References

Beauvoir, Simone de. (2011). The Second Sex (C. Borde & S. Malovany-Chevallier, Trans.). Vintage Books. (Original work published 1949)

Buber, Martin. (1970). I and Thou (W. Kaufmann, Trans.). Scribner. (Original work published 1923)

hooks, bell. (2000). All About Love: New Visions. William Morrow and Company.

Levinas, Emmanuel. (1969). Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority (A. Lingis, Trans.). Duquesne University Press. (Original work published 1961)

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. (1962). Phenomenology of Perception (C. Smith, Trans.). Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1945)

Suggested Reading for Further Reflection

Gilligan, Carol. (1982). In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Harvard University Press.

Noddings, Nel. (2013). Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education (2nd ed.). University of California Press.

Young, Iris Marion. (1990). Throwing Like a Girl and Other Essays in Feminist Philosophy and Social Theory. Indiana University Press.

Katz, Jackson. (2013). The Macho Paradox: Why Some Men Hurt Women and How All Men Can Help. Sourcebooks.

Maté, Gabor. (2022). The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture. Avery.